Hey there every peoples!

Welcome to the second part of my post about how raptors weren’t anything like what they have been built up to be.

Now, let’s talk about the fuzziest area of the raptors image: intelligence. Intelligence is rather hard to define. It is even harder to demonstrate. Dinosaurs have always been thought of as dumb because of the small size of their brains. Raptors were pivotal in breaking that sterotype because of the relative size of their brain (in Jurassic Park 3, Grant claims they were smarter than primates). Of course their brain to body ratio still pales in comparison to that of mammals. Intelligence, contrary to popular belief, isn’t necessarily tied to brain size. It has more to do with the complexity. For example, elephants have a brain 4 times the size of ours and yet we are the ones with mathematics, agriculture, and nuclear weapons. Since brains don’t fossilize, we have to rely on the impressions they left on the inside of the skull. Scans of theropod skulls (none of them raptors, at least that I know of) reveal brains similar to that of alligators, with large areas devoted to sensory perception and smaller areas devoted to information processing. Many birds are the opposite, with large areas devoted to processing information and smaller areas devoted to sensory perception. Dinosaur fanboys trumpet that birds are dinosaurs, but just because some birds show a degree of intelligence (parrots and crows mainly) does not immediately mean dinosaurs were the same. For all we know intelligence may be a mammalian trait, or at least evolved independently in some mammals and some birds.

(here we see an orca actually use bait to capture a bird)

Remember the bite force estimate for Deinonychus? When I first learned about it I was a little confused. Deinonychus has a lightly built skull with thin blade-like teeth. Compare this to mammals that specialize in jaw power like dogs, big cats, bears, sea lions, and even great apes. We find robust teeth, vaulted skulls, wide cheek bones, and of course the characteristic sagital crest. How can animal with no specializations for high bite force have such a stronger bite than animals that do? Then I had a thought: maybe it has to do with brain size? Since mammals have relatively large brains, perhaps they need all the extra hardware to have places to attach those heavy jaw muscles. Reptiles (including dinosaurs) have relatively small brains, so they have more room for jaw muscles. Just my own SWAG (stupid wild ass guess. Of course there is always the chance they misidentified the bite marks). Raptors may have been gifted by dinosaur standards, but right now it looks like it has been greatly oversold.

There is also speed. I don’t know too much about this. It was long assumed that this speed was used in hunting. Speed in animals is usually used to run from predators. When used to hunt, it is usually for short bursts. Wolves and hyenas are endurance runners, wearing their prey out rather than over taking it. However if raptors did indeed hunt smaller animals then there is no reason to think they weren’t fleet of foot. You have to be to catch little critters because they rely on short bursts of speed to escape danger (anyone who has ever tried to catch a lizard or a mouse in their yard knows what I’m talking about)

Now it is time for perhaps the most ambitious claim laid on raptors: social hunting. Social hunting among dinosaurs has been approached cautiously by paleontologists (“just because they are found together doesn’t mean they lived, let alone hunted together”). But somehow raptors have escaped this criticism, despite challenges to the pack hunting paradigm. Fowler and co were not the first. Back in 2007 some researchers decided to re-evaluate the commonly used evidence for pack hunting: bone beds. There are two bone beds known, one from Montana and one from Oklahoma, each containing the remains of a Tenontosaurus and remains from multiple Deinonychus. These were long viewed as kill sites where a pack of Deinonychus brought down a large herbivore, with several of the predators being killed in the process. But, the researchers here saw a very different scene. Instead of focusing on the composition of the animals, they instead looked at what parts were preserved. The Montana quarry preserved the massive tail characteristic of Tenontosaurus and mainly the tails and a few other elements of Deinonychus. The Oklahoma quarry preserved the tail, limbs, and ribs of Tenontosaurus and scant remains of a single Deinonychus. There is no evidence that the raptors had killed the Tenontosaurus.

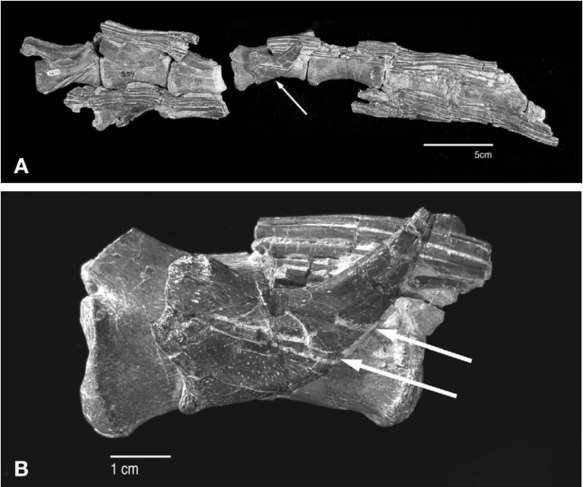

Bonebed containing the remains of the dromaeosaur Deinonychus and the midsized herbivore Tenontosaurus from the cretaceous Cloverly formation of Montana. (from Gignac et al. 2007)

Bonebed containing the remains of the dromaeosaur Deinonychus and the midsized herbivore Tenontosaurus from the cretaceous Antlers formation of Oklahoma. (from Gignac et al. 2007)

They very well could have been scavenging. In fact, the composition of the bones may support this view. The tails in the Montana quarry were left behind because they were the heaviest and hardest to carry away. Same with the elements at the Oklahoma quarry. The fact that the Deinonychus were “butchered” in a similar way to the herbivore suggests they were eaten as well. The authors argue that rather than a coordinated hunt we are actually seeing a feeding frenzy. They draw parallels to modern crocodiles and komodo dragons, who don’t hunt cooperatively but will converge on a carcass to feed. The fierce competition for the best parts often leads to fighting amongst them. This can result in death (especially for smaller and younger animals) in which those animals get cannibalized. This, they argue, explains the nature of the bonebeds and thus it cannot be used as evidence for cooperative hunting.

“Deinonychus antirrhopus distal tail section (YPM 5203) and associated ungual phalanx. A. Underside of proximal portion of a distal tail section in left lateral view, showing a left manual ungual phalanx (III4, marked by arrow) lying against the centrum of caudal vertebra 11(?) and overlain by sections of two of the tail’s elongated chevron processes. Since a diagenetic cause for this unusual association is very unlikely, it may be evidence of combat between two D. antirrhopus individuals at this heavily used feeding site. B. Close up of the left manual ungual phalanx (III-4) overlain by the chevron processes (marked by arrows).” (from Gignac et al. 2007)

The other evidence used for pack hunting is a trackway from China. It shows multiple dromeosaurs all heading in the same direction. Again, this is problematic because the tracks could be individuals passing that way over a period of time. Recently a Utahraptor bonebed, containing animals of all ages, has been found in Utah. It has just recently been moved into a lab for preparation so who knows what it may reveal. But we arrive at the same problem as before: just because they were buried together doesn’t mean they lived (let alone hunted) together.

Cooperative hunting may be a mammal thing. Blah noted that the only two cooperative hunters known today are both mammals: wolves and African hunting dogs. This, however, is a short list (I have to wonder if the authors did their homework). Basically every large canid today lives and hunts together: wolves, African hunting dogs, dohls, and dingos. Even coyotes will occasionally team up to take down larger prey. And there are also other mammals that hunt cooperatively. Lions are well known for hunting in prides (mostly done by the females). Spotted hyenas, once thought to be “stumpy misshapen scavengers” (Jack Horner’s description), hunt together quite effectively. Orcas have different methods for group hunting depending on the prey (be it fish, seals/sea lions, or whales). Finally, chimpanzees work together to hunt small to medium sized mammals (mainly monkeys). This may be permitted by the mammal’s higher degree of intelligence. Chimpanzees and dolphins (which orcas are) have been described as having culture. Dogs are thought of as generally smart animals. Why lions and hyenas hunt cooperatively may be harder to pin down. But the only animals who hunt cooperatively are mammals, which suggests to me it may be due to their intelligence. And of course, you don’t need to hunt in packs when your prey is much smaller than you (per the Fowler hypothesis).

A pack of Utahraptor attacking a sauropod. Such an image may soon be regarded as a relic of the past.

(Like is said, social hunting may be due to a mammal’s higher intelligence. Could dinosaurs have really been capable of the sophisticated planning and coordination employed by these chimps (as they have long been claimed to be)? The likely answer is no, but then again we will never truly know, since behavior doesn’t fossilize)

So, raptors as fierce, intelligent, fast, pack hunting animals seems to stretch the evidence too far. It seems they were rather like their modern descendants. That is to say mostly solitary animals who hunted small prey and were in turn potential prey for others. This means that in North America and Asia during the late Cretaceous tyrannosaurs were the sole megapredators. It was long thought that dromeosaurs were the other ones, using their pack hunting prowess to bring down huge hadrosaurs and ceratopsians. Hell, Jack Horner used to crow how T. rex was nothing but a lowly scavenger while the raptors were the “true predators”. But with the image of the raptor radically changed, that could never have been the case. Besides, pack hunting or not, I fail to understand how a bunch of 50-100 pound animals could bring down something weighing between 3 and 6 tons. Anyway, raptors will continue to be worshiped because they were feathered and also because, well, old habits (or rather perceptions) die hard.

So in the end, it appears raptors don’t live up to the hype. And that’s a good thing. First, that’s just the way science works. We have often found that thinks weren’t what we thought they were. Like Pelagiarctos. It was first characterized as a killer, macropredatory walrus. But new fossils and research showed it wasn’t. Second, animals, should never be subject to hype. We can go on and on about how awesome a creature is, but at the end of the day it’s just an animal. It is bound by the rules of this universe and the laws of nature. Hyping something only serves to blind people to the truth. Not to mention that hype can lead to irrational fanboyism. We’ll see that later when Jurassic World comes out. But in the meantime, don’t think of dromeosaurs as the hyper intelligent, blood thirsty, pack hunting monsters that the popular media has made them out to be. Instead, view them as the unique, mysterious animals they truly are.

Till next time!

Addendum:

I seem to have ruffled some feathers concerning social hunting in animals. but first:

“Crocodilians have demonstrated on a large number of occasions that a large amount can be accomplished problem solving wise even with a small brain.”

Evidence? When it come to proving intelligence the bar is set high. It is apparent that there are varying levels throught the animal kingdom. I hae seen the words “highly” and “intelligent” thrown around a lot (especially by the media). I’m willing to grant crocodiles could be smarter than once thought, but whether they are on par with mammals and birds is another matter.

Now on to the main point, social hunting:

“But Harris Hawks and multiple Crocodilian species are known to cooperate while hunting.”

“Umm … crocs DO hunt co-operatively when going for fish. They even hunt using a specified formation underwater which is a U-shaped net despite the fact that they are known loners. When prey is very abundant or large, crocs WILL co-operate in the kill.”

“Cooperative feeding has been observed in nile crocs, alligators and caiman (the latter two generally in the form of social fishing). Harris’ hawks are also well known for their cooperative hunts.”

The paper i mentioned goes into this quite a bit (i wanted to cover more of it but i have been extremely busy lately). Perhaps not made clear enough, they were specifically testing the claim that dromaeosaurs hunted cooperatively to bring down animals larger than themselves. First crocodiles. They mention the yucare caimans and nile crocodiles. However, they class this as social feeding rather than social hunting. The animals are converging on spots where prey is funneled through some kind of choke point. Social hunting dictates that they actually work together rather than just all show up in the same spot. By this logic grizzly bears perched on rapids to catch salmon is social hunting (rather than social feeding). Again, current evidence points to crocodilians as social feeders (in some species) rather than pack hunters. But if you are so confident that they hunt cooperatively, please enlighten me: how can you tell when it’s social hunting and not a feeding frenzy?

Now they do cite Harris hawks and Aplomado falcons as hunting cooperatively. But again, it’s not on par with mammals. The main differences are twofold. The first is that they are going after prey that could be taken by a single bird. The other is that the goal seems to be increasing their success rate, as opposed to providing more food by killing a much larger animal. This could be seen as analogous to chimpanzees, since they hunt animals much smaller than themselves. But it could be argued that it is more, since it does involve working together to catch an animal that a lone chimpanzee could not (monkeys are much faster and more agile climbers than chimps. Only by working together can chimps actually catch them).

Social hunting is seen in only two species of one group of birds (raptors). But social hunting is seen in multiple species across several groups of mammals (dogs, cats, hyenas, dolphins, and chimpanzees). The paper argues (based on other research) that cooperative hunting in mammals is likely the product of group living, not the cause. Mammals do form sophisticated social groups, and many have even been classified as having culture (the great apes, elephants, cetaceans). They say this could be, in part, due t the very prolonged and deep bond between the mother and her offspring. Long story short, behavior and intelligence are very complex and hard to pin down. Applying it to any animal because carries a hefty burden of proof. But right now it’s say mammals are still on top in that category (for the time being).

Now there were a couple other tidbits that need addressing. The first:

“I would suggest studying mammalian kills which are the result of pack hunting especially where 1 or more predators might be killed. See what you have left [a taphonomic study if you will] and try and discern the cause of death from only the bone evidence”

Taphonomy isn’t just about how the animal died, it’s about what happened to it from when it died to when it was buried. The composition of the bone beds argue for an agonistic feeding frenzy. Did you not see the picture of a Deinonychus hand claw stuck in the tail of another Deinonychus and how it could be evidence of a fight? Contrary to popular belief predation accounts for only a small amount of deaths in any ecosystem. Animals more commonly die due to disease, exposure, parasites, intraspecific conflict, or sometimes they just have an accident. It is hard to imagine any of those coming into play at a feeding site. Competition for food is usually fierce. Even animals that hunt cooperatively often have strict feeding hierarchies. Hyenas were long thought to use their strong jaws to scavenge carcasses. But we now know it is to tear a chunk (bones, cartilage, everything) off a carcass and then eat quickly in seclusion to avoid competition with the rest of the clan. Given the agonistic behavior exhibited by crocodiles and komodo dragons, it is likely that is what was going on in the Deinonychus bonebeds.

(As a perfect example of how important taphonomy is: in the National Geographic show “Dino DEath Match”. Robert Bakker argued for pack hunting in “Nannotyrannus” based on shed teeth found with a Triceratops. He indicated (by standing next to a cast of it) that the Triceratops is the specimen known as “Kelsey”. The Black Hills Institute (who excavated and sells casts of Kelsey) sell a poster showing the skeleton as it was found. Now Bakker says that found with Kelsey were 30 shed Nannotyrannus teeth. He says this is evidence of pack hunting because one animal couldn’t have shed that many teeth. But if we look at the skeleton of Kelsey, we see there is a much more likely explanation. While largely complete, Kelsey’s skeleton is jumbled and mixed up. This suggests it was around for a while before being buried. This allowed plenty of time for single Nannotyrannus to visit the carcass over a period of time.)

“I may be a trait more commonly seen in mammals today, but archosaurs would seem to be capable of it as well. They may well have pioneered it, with us mammals being the Johnny-come-latelies.”

But to what extent? We have established that while a couple bird species are social hunters, it’s not on the same level as mammals. How do you know those birds aren’t merely the exception? suggesting an animal is capable of something and actually demonstrating are two different things entirely. Proving that ancient animals were social hunters is a very tall order. Especially dinosaurs since they have hardly any modern analogues. Smilodon and various extinct species of dogs are often suggested to be social hunters but we still have to exercise caution because we still don’t know how to quantify it. And sometimes it’s not about who pioneered something. It can sometimes be about who refined it, took it to the next level. And it looks like that’s what mammals did.

“Reptiles (including dinosaurs) have relatively small brains, so they have more room for jaw muscles. Just my own SWAG (stupid wild ass guess. Of course there is always the chance they misidentified the bite marks). Raptors may have been gifted by dinosaur standards, but right now it looks like it has been greatly oversold.”

Crocodilians have demonstrated on a large number of occasions that a large amount can be accomplished problem solving wise even with a small brain.

“But the only animals who hunt cooperatively are mammals, which suggests to me it may be due to their intelligence. And of course, you don’t need to hunt in packs when your prey is much smaller than you (per the Fowler hypothesis).”

But Harris Hawks and multiple Crocodilian species are known to cooperate while hunting. I’m not trying to dispute your point that the media has over sensationalized it’s just some of your arguments are not correct. One of my biggest questions with raptors has always been where did the idea of them being such good jumpers come from. I have never been able to find a single paper illustrating the bio-mechanics of dromaeosaurid jumping.

Umm … crocs DO hunt co-operatively when going for fish. They even hunt using a specified formation underwater which is a U-shaped net despite the fact that they are known loners. When prey is very abundant or large, crocs WILL co-operate in the kill. I would suggest studying mammalian kills which are the result of pack hunting especially where 1 or more predators might be killed. See what you have left [a taphonomic study if you will] and try and discern the cause of death from only the bone evidence.

I also agree with your view that coyote sized predators bringing down 3 ton hippo sized prey is pretty ridiculous. One would need 25 of these animals to attack one limb to bring prey that size down. By that time, one still has to kill it while much larger predators will have arrived on the scene

by then.

Cooperative feeding has been observed in nile crocs, alligators and caiman (the latter two generally in the form of social fishing). Harris’ hawks are also well known for their cooperative hunts. I may be a trait more commonly seen in mammals today, but archosaurs would seem to be capable of it as well. They may well have pioneered it, with us mammals being the Johnny-come-latelies.