Hey there every peoples!

With Jurassic World just around the corner, I thought I would do something to go along with it. I have a lot of words about the fanboys, but that will come after the movie premiers. So what shall we talk about? Well with the impending release of a Jurassic Park sequel there has been chatter about how much the first one changed our perception of dinosaurs. So why don’t we talk about that. Specifically, the franchise’s main villain.

No, not the T. rex. While a brutal killing machine, it did save our heroes at the end of the movie. No, I am of course talking about the Velociraptor (or raptors for short). Jurassic Park made Velociraptor a household name. It introduced people to a then little-known family of dinosaurs called dromaeosaurs. This group is characterized by light builds, long stiff tails, and a enlarged claw on the second toe of each foot. At the time Jurassic Park was made, there were only a few species known mostly from fragmentary remains. Velociraptor was the best known, thanks to the many marvelous fossils found by Roy Chapman Andrews’ expeditions to the Gobi. The largest then known was Deinononychus, who measures 10 feet long, 3 feet tall, and weighed as much as 150 pounds.

Unfortunately, that still wasn’t big enough to properly menace humans. Plus Deinonychus just didn’t sound as cool as Velociraptor. So the film makers fudged it and blew Velociraptor up to 20 feet long and 6 feet tall. The dinosaur was portrayed as extremely fast and highly intelligent (the 3rd movie even went so far as to say they were smarter than primates). The raptors were now the perfect match for us mighty humans. But just as production wrapped up, a discovery over in Utah upped the ante on dromaeosaurs. Dubbed Utahraptor (such an inspired name) it was the size of the raptors depicted in the film!

Unfortunately it was too late and the movie cemented the image of Velociraptor as a big, speedy, hyper intelligent super predator.

That’s right. We can run fast as a cheetah, jump 10 feet into the air, maul and eat a cow in 20 seconds, set traps, open doors, file our taxes early, predict the weather correctly, and beat Battletoads without losing a single life! (image from Jurassic Park Wiki)

John Ostrom, the namer of Deinonychus, was the first to push the idea that raptors were swift, fierce hunters who attacked in packs to bring down prey larger then themselves. Jurassic Park, while a work of fiction, only solidified that perception. Two bonebeds in North America preserving multiple Deinonychus were used as evidence that raptors were group hunters. Artwork even began to spring up showing Utahraptor ganging up on small sauropods. They were discussed as being the nastiest and most vicious of dinosaurs, tearing into their prey enmasse, slashing open huge wounds with their trademark “killing claws”. While T. rex and other large theropods were depicted as pondering hulks who used brute force to bring down prey, raptors were portrayed as swift, smart, and ruthless predators.

Jack Horner particularly championed this view. He used this perception of raptors to justify his view of T. rex as a scavenger. He even said in a debate/panel at the Natural History Museum in London: “I’d rather be locked in a room with four lions and a tiger than one little Velociraptor. Because I figure that Velociraptor is probably going to eat half of me before it kills me.” Raptor hype had reached an all time high. But then some began to challenge this view. Were raptors really as fast and smart and vicious and deadly as pop culture would have us believe? After over a decade of scientific research, the answer appears to be: no.

Because if it’s not like a raptor, then it MUST be a scavenger. Said only one guy ever. (from Technology.com)

Let’s start with the most famous aspect of raptors: the “killing claw”. Heavily curved and apparently sharp on the inside, these claws were carried off the ground on the second toe of each foot. The claw was likened to a switch blade. When attacking, the raptor would latch on to its prey and slash with both claws. This would create huge lacerations that would then cause the animal to bleed to death. And so raptors were portrayed eviscerating their prey without mercy (and without any thought to whether or not this was actually the case). In 2005, Manning et al. put this idea to the test. They created a synthetic raptor claw and attempted to use it to slash at a piece of pork and a section of alligator hide. The claw sunk into the pig flesh but failed to create a deadly slash. Against the alligator hide the tip of the claw actually broke off, leaving the skin untouched. Manning and his colleagues concluded that the claw was instead used to climb up larger prey, with the raptors using their sharp teeth to inflict trauma. Some artistic impressions followed suit on this new idea.

It was also hypothesized that the claw could be used to pierce the vital organs of smaller prey. As evidence they pointed to one of the most spectacular fossils ever found: the fighting dinosaurs. Discovered in the Gobi Desert, the fossil shows a Velociraptor and a Protoceratops locked in combat. The Protoceratops clamps down on the raptors arm with its powerful beak. The Velociraptor latches on to the frill of the Protoceratops with its other hand and the killing claw is thrust into the neck of the Protoceratops.

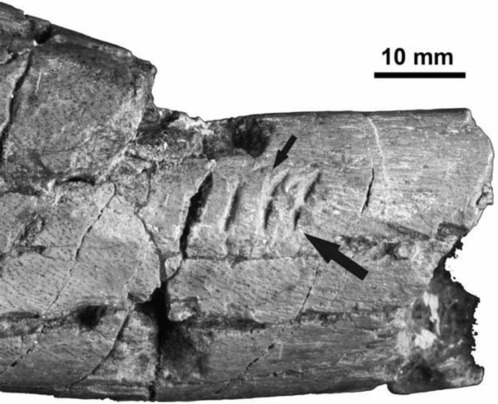

While a truly unique fossil, we don’t know if this was a regular occurrence or if the Velociraptor was attacking the Protoceratops out of desperation. But it did provide the rarest of evidence: clear evidence of predation. But with the killing claw in doubt, how did these animals kill prey larger than themselves? A study into raptor bite force suggests they may have relied on their teeth and jaws to inflict damage. In 2010 Gignac and colleagues attempted to estimate the bite force of Deininychus based on bone puncture marks. They started with several bite marks found on the bones of a Tenontosaurus (a medium-size herbivore from the early Cretaceous of North America, the same time and place as Deinonychus). They made casts of the tooth marks and compared them to known carnivores of the time. Deinonychus was the best match. They then proceeded to use casts of Deinonychus teeth to puncture a cow bone. They would keep increasing the force until the tooth broke through the bone. The results were surprising. Based on the types of tooth marks and the experiment with the cow bone, they arrived at figures of 4100 newtons and 8200 newtons. That is far greater than any modern mammalian carnivore. With strong jaws and blade-like teeth, Deinonychus (and perhaps other dromaeosaurs) could cleave off chunks of flesh, causing grievous injuries to prey. But a more recent hypothesis challenges the image of dromaeosaurs as the savage big game hunters altogether.

Dromaeosaurs are one of the closest relatives of birds. For a long time now the link has been well known: hollow bones, wishbones, and even feathers (for starters). The bird link has been mostly anatomical. Then in 2011 Fowler et al. released a radical new version of the dromaeosaur, one that hunted more like a bird than a wolf. They note that modern birds of prey kill small prey with an enlarged second toe claw. They use their claws to puncture into prey, not only securing it but also causing crippling wounds. The birds take their new found meal to a safe location (usually up in a tree) and begin to eat the animal while it is still alive, tearing it apart with its beak. Fowler and his colleagues propose the same for dromaeosaurs. They cite the weak jaws (perhaps Deinonychus was just the exception) and the similarity of their killing claw to that of birds of prey. They propose that dromaeosaurs used their body to pin down prey, incapacitating it with their killing claws. They then proceeded to eat it alive. Fowler et al. suggest that the dromaeosaurs, while not being able to fly, could have flapped their arms (which were feathered) to steady themselves and maintain their position on top of their prey. Since this method of feeding requires body weight to subdue prey, it limits the size of animals they could tackle. The largest dromaeosaurs (Utahraptor and Achilobataar) may have preyed on animal no bigger than a few hundred pounds. Perhaps they specialized in attacking the young/juveniles of herbivores.

This new view is a serious detriment to the popular idea of raptors as pack hunting animals who took on prey bigger than themselves. There is another serious blow to that idea but we’ll get to that later.

very interesting, thanks Doug